On 18 May 2011, Claire Bishop gave the first in a series of talks sponsored by Creative Time. The lecture series provides a context for CT’s fall exhibition Living as Form, a “project that explores over 20 years of cultural works that blur the forms of art and everyday life, and emphasize participation, dialogue, community engagement, and activism around social issues”. [From the website for Living as Form.] CT’s project is part of a much larger critical response to the “social turn” in art, to which Claire Bishop has contributed a number of publications and critical analyses.

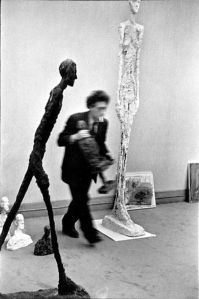

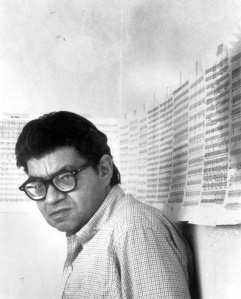

Christoph Schlingensief, "Please Love Austria", 2000

In her lecture, “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?”, Bishop makes an appeal for artistic practices that critically engage social and political phenomena, without compromising their status as art. What follows is a summary sketch of Bishop’s lecture based on my notes. Fortunately, the full presentation, with a Q&A following, has been posted on the CT website. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes below are from Bishop’s lecture.

Four Observations

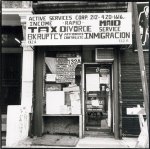

Bishop begins informally with four observations that come out of her recent participation in a discussion organized by Tania Bruguera, as part of Bruguera’s Immigration Movement International, sponsored by CT and the Queens Museum of Art.

1. In discussions of social practice today, the term “art” tends to drop out of the picture — the emphasis shifting to “practice”, a term typically understood to denote an ongoing process which takes precedence over the making of objects.

2. The standard triad of artist—work of art—audience is also re-conceived as producer of situations [cf. Jeremy Deller’s claim “I don’t make things, I make things happen”], project (an ongoing process, often with an unclear beginning and end), and participant (as collaborator or co-producer). This approach and shift comes as a challenge to traditional modes of artistic production and consumption under capitalism, and thus to art history, exhibition making, and spectatorship. As a result, the performative dimension (lecture, panel discussion, conference) supersedes the exhibition of objects.

3. Mediation — the visual aspect and aesthetics typically associated with art — is not addressed by the artists and, thus, tends to drop out, as well. Nor is much attention given to follow-up in the communities where the art/social interventions take place.

4. Artists engaged in social practice adopt an “antinomic” relation to visual art. But given that most of their projects are endorsed by visual arts organizations, the claims of these artists to stand outside the art world are “disingenuous”. The institutionalization of social practice is also found in the large number of MFA programs popping up in the U.S. and the prizes targeted toward social practice.

What, Bishop seems to ask, are we to make of all this? To answer that question we need a broader historical perspective.

Spectacle — Participatory Art’s Adversary Since the 1960s

Looking back through the 20th century, we find participatory art opposing itself to spectacle, with the realm of images compromised by market capitalism and presented in ways that minimize viewer engagement and agency. Participatory art in this situation sees itself as an antidote to alienation, repression, and the numbing effects of mainstream culture.

Artists’ motivations for pursuing socially participatory practices tends to be underwritten by a common claim — “Contemporary capitalism produces passive subjects with very little agency or empowerment.” This concern, for example, is the focus of Guy Debord’s Marxist critique of late modern culture of the spectacle, which is organized around alienating forms of capitalist production. “Given the market’s near total saturation of our image repertoire, so the argument goes, artistic practice can no longer revolve around the construction of objects to be consumed by a passive bystander. Instead, there must be an art of action, interfacing with reality, taking steps, however small, to repair the social bond. As the French philosopher Jacques Rancière points out, ‘The critique of the spectacle often remains the alpha and omega of the politics of art.’”

What do we mean by “spectacle”? In the writings of critics associated with October it takes on a number of characteristics. For Rosalind Krauss, writing about late capitalist museums, spectacle includes “the absence of a historical positioning and a capitulation to pure presence”; for James Meyer, writing about Olafur Elliason’s Weather Project, “it denotes an overwhelming scale that dwarfs viewers and eclipses the human body as a point of reference”; for Hal Foster, “writing on the Bilbao Guggenheim, it denotes the triumph of corporate branding”; and for Benjamin Buchloh, “denouncing Bill Viola, it refers to an uncritical use of new technology”. For Guy Debord, spectacle denotes not works of art but social relations under capitalism and under totalitarian regimes. This characterization of the spectacle is followed by futher elaboration of the critiques of Debord, Jean Baudrillard who claims the society of the spectacle has come to an end, and Boris Groys who argues that we’ve reached an age of “the spectacle without a spectator”.

Participatory art sees the present as calling for “a new understanding of art without audiences, one in which everyone is a producer”. But the audience cannot be entirely eliminated — the audience is, in some sense, always there. Not everyone can be a participant.

The new approach to the audience is against contemplation and passivity. Collective, co-authoring and social engagement is the goal. This has been attempted, for example, through constructivist efforts to oppose injustice and proposing an alternative, or “through a nihilist re-doubling of alienation, which negates the world’s injustice and illogicality on its own terms”. While both seek participation and collaboration, one does it affirmatively “through utopian realization”, the other indirectly or negatively “through what we might call the negation of negation”.

The array of participatory works in the 20th century cuts across boundaries separating the left and right — futurism and constructivism, Paris Dada, the Situationist International and Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, Happenings (negation of negation), and with different meanings, forms, and effects in Argentina, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, and England.

In short, the anti-aesthetic refusal today is not a radical break but a kind of continuation of the recent past.

Analysis of Artistic vs. Social Criteria

Anti-aesthetic refusal characterizes many recent participatory projects. Several binaries, e.g. art vs life, underwrite these attempts to go beyond art to affect social and political change.

There’s a question, Bishop notes, that’s repeatedly raised: “Surely it’s better for one art project to improve one person’s life than for it not to happen at all.” To get some critical distance, Bishop asks what that question is a symptom of and finds it’s related not just to the (false) dichotomy of “art vs. real life”, but to several additional binaries currently in play — equality of access to the work of art versus quality of the resulting project, as well as participation and spectatorship — all of which reveal that “artistic and social judgments don’t easily merge, indeed they seem to demand different criteria”. This problematic comes up repeatedly today in discussions of participatory art and social practice. Humanist ethics are evoked in the social discourse, but eschewed in the artistic discourse. Art is accused of being focused exclusively on reflection and representation of the world and, thus, amoral and ineffective, while the social discourse is accused of “being stubbornly attached to existing categories and focusing on micropolitical gestures at the expense of sensuous immediacy as a potential locus of disalienation”. The overriding tension here is between morality and freedom.

Next comes a theoretical elaboration on this binary opposition as it appears in a recent analysis of the critique of capitalism by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello. Bishop draws on their fundamental breakdown of artistic and social critique.

———————

Filling in a bit here and to highlight some of the key issues in Bishop’s argument, I’m inserting the following excerpt from Sebastian Budgen’s review of The New Spirit of Capitalism in the New Left Review (January-February 2000). Note that Budgen’s review is not mentioned in Bishop’s presentation.

[The book’s] starting point is a powerful statement of indignation and puzzlement. How has a new and virulent form of capitalism — they label it a ‘connexionist’ or ‘network’ variant — with an even more disastrous impact on the fabric of a common life than its predecessors, managed to install itself so smoothly and inconspicuously in France, without attracting either due critical attention or any organized resistance from forces of opposition, vigorous a generation ago, now reduced to irrelevancy or cheerleading? The answer to this question, Boltanski and Chiapello suggest, lies in the fate that overtook the different strands of the mass revolt against the Gaullist regime in May–June 1968.There have always been, they argue, four possible sources of indignation at the reality of capitalism: (i) a demand for liberation; (ii) a rejection of inauthenticity; (iii) a refusal of egoism; (iv) a response to suffering. Of these, the first pair found classic expression in bohemian milieux of the late nineteenth century: they call it the ‘artistic critique’. The second pair were centrally articulated by the traditional labour movement, and represent the ‘social critique’.

These two forms of critique, Boltanski and Chiapello argue, have accompanied the history of capitalism from the start, linked both to the system and to each other in a range of ways, along a spectrum from intertwinement to antagonism. In France, 1968 and its aftermath saw a coalescence of the two critiques, as student uprisings in Paris triggered the largest general strike in world history…. Gradually, however, the social and the artistic rejections of capitalism started to come apart. The social critique became progressively weaker with the involution and decline of French communism, and the growing reluctance of French employers to yield any further ground without any return to order in the enterprises or any increase in dramatically falling levels of productivity. The artistic critique, on the other hand, carried by libertarian and ultra-left groups along with ‘self-management’ currents in the CFDT (the formerly Catholic trade-union confederation), flourished. The values of expressive creativity, fluid identity, autonomy and self-development were touted against the constraints of bureaucratic discipline, bourgeois hypocrisy and consumer conformity. […]

Capitalism is conceived here, in Weberian fashion, as a system driven by ‘the need for the unlimited accumulation of capital by formally peaceful means’, that is fundamentally absurd and amoral. Neither material incentives nor coercion are sufficient to activate the enormous number of people — most with very little chance of making a profit and with a very low level of responsibility — required to make the system work. What are needed are justifications that link personal gains from involvement to some notion of the common good. Conventional political beliefs — the material progress achieved under this order, its efficiency in meeting human needs, the affinity between free markets and liberal democracy — are, according to Boltanski and Chiapello, too general and stable to motivate real adherence and engagement. What are needed instead are justifications that ring true on both the collective level — in accordance with some conception of justice or the common good — and the individual level. To be able truly to identify with the system, as managers — the primary target of these codes — have to do, two potentially contradictory longings have to be satisfied: a desire for autonomy (that is, exciting new prospects for self-realization and freedom) and for security (that is, durability and generational transmission of advantages gained). [emphases added.]

———————

Bishop’s Concluding Summary Argument

1. Distinction Between Artistic and Social Critique

Drawing on the historical and philosophical writings of Jacques Rancière, Bishop builds a case for sustaining the tension between spectacle and participatory practice and the distinction between art and everyday life, rather than blurring these distinctions.

Bishop’s concluding argument begins with a survey of twentieth century activist and avant-garde works of art that employ various participatory, interventionist, and often “spectacular” tactics, giving particular emphasis to the group of artists brought together in Tania Bruguera’s Useful Art event (23 April 2011)— Mel Chin, Rick Lowe, Not an Alternative (Beka Economopoulos), Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, and Pase Usted (Jorge Munguia).

The claim that emerges from this overview is that “the most striking projects…unseat all of the polarities on which this discourse [of participatory art] is founded — individual vs. collective, author vs. spectator, active vs. passive, real life vs. art — but not with the goal of collapsing them”. Christoph Schlingenspiel’s Please Love Austria performance from the Vienna International festival of 2000 is singled out as an example of participatory art that manages to make productive use of these polarities.

2. Distinction Between Democracy in Art and Democracy in Society

Bishop contends that the tension between artistic and social critiques today is, in large part, derived from a desire to sustain some measure of autonomy in art, while simultaneously engaging real world concerns and recognizing the role of the spectator as a creative agent. This entails, at the very least, confronting the paradox noted by Rancière “between the logic of art that becomes life at the price of abolishing itself as art, and the logic of art that does politics on the explicit condition of not doing it at all”. [Jacques Rancière,“Problems and Transformations in Critical Art”, which appears in Bishop’s anthology, Participation.]

Rather than allowing the work of art to drop out of the picture by giving way to political action, the work must be sustained as “a mediating object — a spectacle that stands between the idea of the artist and the feeling and interpretation of the spectator…. The artist relies upon the participant’s creative exploitation of the situation that he or she offers, just as participants require the artist’s cue and direction.”

An underlying assumption here is that social practices (critiques) do not have the same structure as artistic practices. Bishop suggests that the disparity follows from the fact that forms of democracy in art do not have an “intrinsic” relation to the forms of democracy in society. Artistic criteria are more “paradoxical”.

3. The Historical Nature and Limits of Artistic Participation

To bridge the gap separating artistic production on the one hand and social change on the other, Bishop argues, artists would benefit from aligning with actually existing political organizations. Such connections, well established in historical avant-garde movements of the past, have been lost today, giving way to a kind of free-floating anti-capitalism. “As a consequence,” Bishop claims, “artists have internalized a huge amount of pressure to bear the burden of devising new models of social and political organization, a task that artists are not always best equipped to undertake.” Part of the solution, according to Bishop, would be “a viable international alignment of leftist political movements and the reassertion of art’s inventive forms of negation as valuable in their own right”. This would involve re-positioning art as a source of representation, critique, and experimentation that engages the public and contributes to politically progressive projects.

Problems and Prospects

There’s considerable room for debate about the details, and for some, I suspect, Bishop’s fundamental approach. In various ways, her argument sharpens the focus on concrete, as well as theoretical, issues about the interpretation, nature, and effectiveness of “social practice”.

- In what sense can we talk about “democracy” in art?

- How, and to what extent, does it differ from citizenship and democracy in society?

- Are the two linked, as they must be if artistic activity has the capacity to inform social and political change?

- What can we conclude about the nature of the relationship between art and social critique beyond acknowledging art’s complexity and paradoxical criteria?

- And how are we to understand the relationship of art and ethics? Are they parallel to one another, similar in structure but focused on different phenomena, interests, and needs?

- Can they work productively together?

- What do we risk in conflating them?

These are crucial issues, discussion and analysis of which goes well beyond the constraints of a public lecture on recent trends in contemporary art. As it was, Bishop’s talk moved briskly, covering both theoretical and practical issues. Fortunately, the discussion will continue with subsequent talks and the release of her forthcoming book, Artificial Hells, from Verso Press, on which the Creative Time lecture was based.

Conclusion

I have the sense — and it’s no more than a vague notion — that artistic attempts at “social practice” have great difficulty gaining the traction they need in the social world to produce substantial long term change.

The social world is not the art world. They’re materially different, demanding distinct and important things from us. We need to exercise practical intelligence to grasp those demands and to act in ways that enable us to make productive contributions. This is one of the things that distinguishes art from “mere” entertainment.

Consider the distinction between imagining things as being other than they are and making things be other than they are. Imagination is a key, perhaps essential, element of art. And it’s a characteristic that also plays an important role in ethics and social relations. This is just one of the many points at which art and ethics overlap. When characteristics overlap in this way, the boundaries between the two realms is blurred, making it easier to overlook the differing needs, interests, strengths, and weaknesses of each realm.

So the response from those engaged in art, it seems to me, is not to avoid the ethical dimension, but to understand how art can contribute to progressive social change by drawing on its strengths — as art.